The Great British Book Race – Children’s Reading Statistics

Reading is a basic key skill that when nurtured and encouraged forms the very heart of a child’s character and childhood memories.

However, the rise in screen time, the closure of libraries and changing family dynamics has changed our reading habits. To understand the impact this is having on our children we’ve undertaken some extensive research to discover when they’re reading, what they’re reading, and the social, economic and health impact of these changes. In the process we’ve uncovered some interesting trends and children’s book statistics.

We based our survey on a 2000-strong study group of parents from across Great Britain. Hailing from diverse backgrounds, in order to have a clear picture of the reading facts and figures of primary school-age children.

THE RETURN OF THE CHILDREN’S CLASSIC

Interestingly, our research revealed the nation’s favourite children’s books are those written long before today’s generation’s grandparents were born.

Forget Harry Potter, Hunger Games or The Gruffalo – the best children’s books are classics from the 1940s and beyond.

In our deep dive into children’s books, our statistics revealed Enid Blyton’s classic Famous Five series is the nation’s top choice – the first of which was published in 1942.

CS Lewis’ The Lion, The Witch And The Wardrobe was the second most popular – despite being written in 1950. While third was the even older Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett, which dates back over 100 years to 1911.

Collectively Roald Dahl is still the most popular children’s author with Matilda, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, James and the Giant Peach and Fantastic Mr Fox standing? the test of time. As a result Roald Dahl made it onto the top 10 list three times with The BFG (1982) at number four, Matilda at number seven and Charlie And The Chocolate Factory (1964) at number eight.

Google trends’ data supports this theme – with Roald Dahl still being the most searched for children’s author in the last 12 months – beating JK Rowling, Jacquline Wilson, Julia Donaldson, and Enid Blyton.

The top ten most popular children’s books were recorded as follows:

- Enid Blyton’s classic Famous Five

- CS Lewis’ The Lion, The Witch And The Wardrobe

- Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett,

- The BFG (1982) Roald Dahl

- The Faraway Tree (1943)

- The Hobbit (1937)

- Matilda (1988)

- Charlie And The Chocolate Factory (1964)

- The very Hungry Caterpillar

- Charlotte’s Web (1952)

THE DEMISE OF FAIRY TALES

However, while children’s authors have stood the test of time, fairy tales written more than two centuries ago are deemed irrelevant by most.

Our report revealed that one in ten parents don’t bother with outdated fairytales at all – however of those that do a third admit to making the tales more relevant to modern life by replacing characters with more modern day alternatives.

Prince Harry was a common replacement (13 per cent) followed by Ed Sheeran (10 per cent), David Walliams (7 per cent), Holly Willoughby (6 per cent), Mo Farah (5 per cent), and Harry Kane (4 per cent).

The moral of a story may be timeless, but the fairytale considered the most outdated by parents are Sleeping Beauty (17 per cent), Rumpelstiltskin (15 per cent), Hansel And Gretel (14 per cent), Cinderella (13 per cent), Snow White (13 per cent), and The Princess and The Pea (11 per cent).

Delving into the research further, parents feel that parts of these stories need changing as a quarter are worried about what their children might think of the real endings (26 per cent).

Over a third (36 per cent) feel that the morals are wrong and that they don’t represent modern day life anymore.

The themes that mums and dads feel are in need of inclusion in modern-day moral stories

for their children include: the importance of being independent (30 per cent), not being pressured to look a certain way (27 per cent), not seeking to live ‘happily ever after’ (25 per cent), multiculturalism (21 per cent), feminism (18 per cent) and the impact of social media on today’s society (13 per cent).

RISE IN BOOK SALES

Last year overall book sales revenue in the United Kingdom was recorded as down during 2018, according to Statista, an industry authority.

However, in the face of this decline, sales for children’s books and non-fiction were up.

Publisher sales for take home physical children’s books was recorded to have reached £242million in 2018 – with 191 million books sold in the UK. This was up from £239 million in 2017.

Sales of hard copy books saw a dramatic decline between 2009 and 2014 – with adult fiction declining by £150million. The cause of the hit to the market was placed at the rise of e-books, with more and more Brits migrating towards Kindles as their preferred method of reading.

However, even then, sales of children’s books continued to rise with parents, teachers and children casting technology aside, reaching for hard colourful copies to engage imagination instead.

Despite warnings of increased screen time, cuts to library services and a lack of books in schools meant in 2018 one in three books bought were kid-lit.

BOOK POVERTY

Children are reading less than ever before. Research in 2019 by the National Literacy Trust shows that in 2019 just 26% of under-18s spent some time reading. This is the lowest level since the charity first surveyed reading habits in 2005.

This figure is stark, against a context of growing book poverty. In November 2018 the National Literacy Trust revealed 383,775 children in the UK don’t own a single book of their own. Yet when children who do own a book are six times more likely to read above the level expected of their age.

Against this decline, Labour research in 2019 showed that the number of books borrowed from libraries in England has dropped from 255,128,957 in 2011 to 157,387,109 in 2018 – a 38% decrease.

This decline comes against a backdrop of library closures, with more than 700 closed since 2010 according to Library Campaign.

SOCIO-ECONOMIC AND HEALTH BENEFITS OF READING

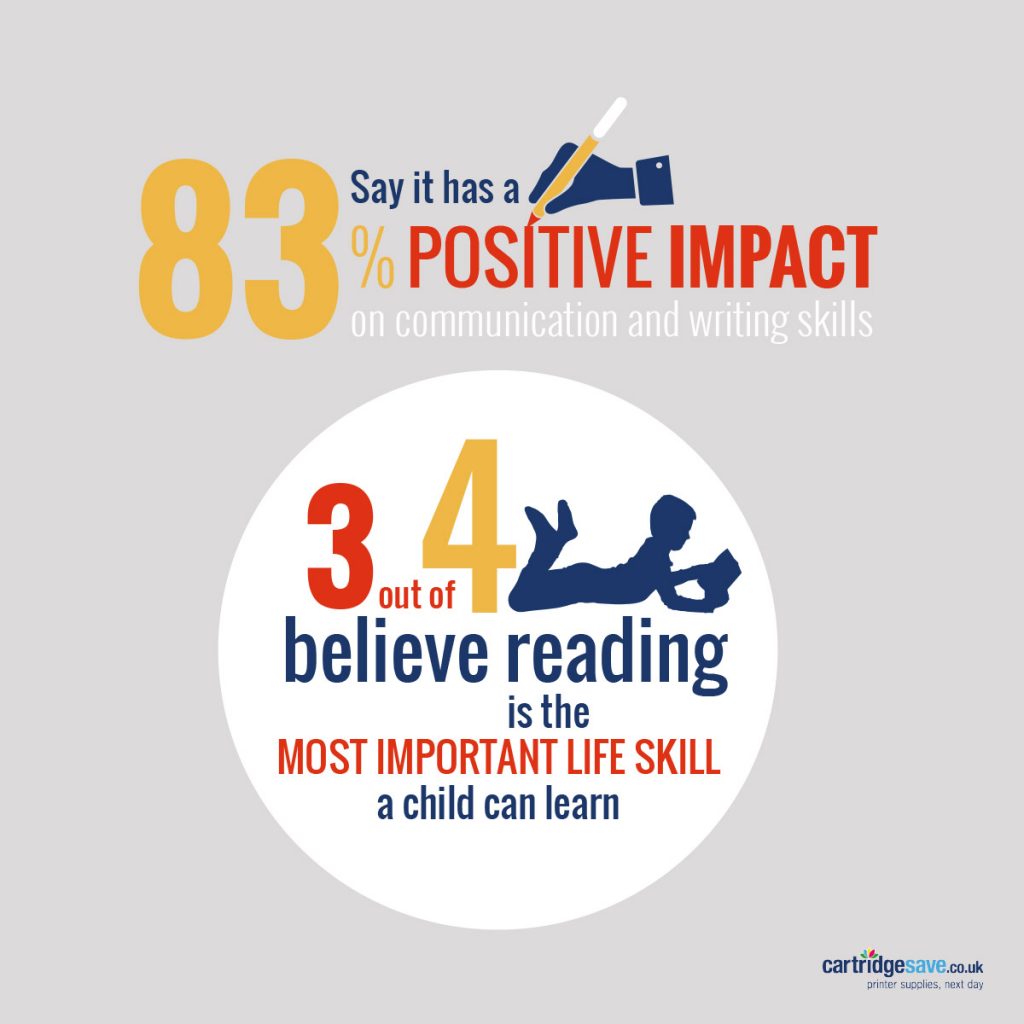

The reading statistics we collated also suggests that learning how to read the printed word has a major impact on developing other abilities, which are pivotal to success in later life – with 83 per cent saying it had a positive impact on communication and writing skills.

The data also revealed three quarters of those surveyed (74 per cent) believe reading is the most important life skill a child can learn.

This supports research in 2013 by the The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), that shows that in England the median hourly wage of workers with the highest levels of literacy is 94 per cent higher than for workers who have the lowest levels of literacy. The same report revealed that literacy has been found to have a relationship with depression. 36 per cent of those with low literacy were found to have depressive symptoms, compared to 20 per cent of those with the highest levels of literacy.

A similar report in 2013 by Sullivan and Brown (2013) states in their Social inequalities in cognitive scores at age 16: The role of reading concluded that reading for pleasure is more important for children’s cognitive development than their parents’ level of education and is a more powerful factor in life achievement than socio-economic background.

In their follow up analysis in 2014 they deduced that low levels of literacy cost the UK an estimated £81 billion a year in lost earnings and increased welfare spending impacted on the economy as a whole.

END